Light, it can be waves or particles, we can see it, and feel it, but we can’t touch it, it’s a funny old thing really, and yet as photographers, we are capturing this stuff every day.

The sun appears to be constantly changing, in both height and angle, although the sun is stationary(ish) and we’re the ones moving about. Generally, it rises in the east and sets in the west, although if you’re in far north of beautiful planet earth at this time of year it will rise more in the north east, and sets in the north west.

The appearance of the sun changes too when it’s low in the sky, it looks bigger and has more of the atmosphere to shine through so its colour and intensity change. If it’s a clear sunny day the light is raw and harsh. I know what you’re thinking, hot sunny days are nice, there’s nothing harsh about them unless you’re in a desert. Unfortunately, there is in photography, and that’s the shadows.

Like every other past-time, be that sailing, golf or cycling, photography has its own language and terminology. Photographers can talk about the quality of light, its temperature, whether it’s hard, or soft etc. but what does that really mean? Let’s start today with how hard light is. If we can’t touch something how do we know how hard it is? The hardness of light is down to the graduation between light and dark. On bright sunny days, the light is hard, because it creates a hard line between light and dark where the shadows form.

I’ve taken this cat figure into the studio to show the difference, let’s shoot it with hard light:

In this shot, the light is hard, the shadow under the cat’s chin, caused by it’s haunch, is solid. This was shot using one light, similar to the effect you’ll get from the sun in a clear sky. The light is travelling straight from the source to the subject there is nothing in its way to interfere or change or alter it, it’s light in its raw undiluted form. As such, it leaves straight, harsh, shadows, no grey area, it’s either black or white. Of course, things can be done to lighten the shadow area with second fill in lights and reflectors etc, but the line between light and shadow will remain sharp and crisp.

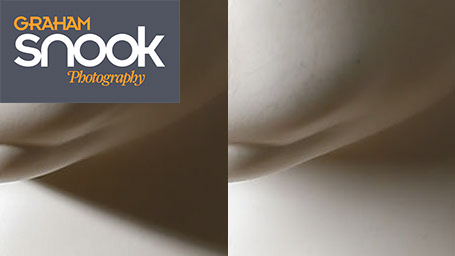

If we cover the light source with a thin translucent fabric, reflect or in this case shoot with a softbox, the light is defused and the shadows soften. The translucent fabric does a number of things: it reduces the intensity of the light slightly, it makes the light source bigger and it defuses (or scatters) the light. Gone is the sharp contrast between light and shadow, it’s now been replaced by a soft gradient from light to dark. While it’s true that the sun is a very big source of light, it’s also very far away, so it’s the size of the light source relative to the subject that we’re interested in. So if we take a close-up look, it’s easy to see the difference.

If the light becomes too soft it becomes flat, because it’s so defused it has lost all its directional qualities and its ability to highlight texture or form in the subject, making them look, well…flat. Nature does this by herself, using clouds. The clouds act like translucent fabric scattering the light in all directions and angles so there is no longer a hard line between what is light and what is dark. With a light layer of cloud you’ll still get form. If the clouds are thick, this gives us very flat uninteresting lighting, you can shoot in one direction, turn 180 degrees in the opposite direction and still get the same lighting.

Soft lighting is usually flattering for the subject, hiding skin imperfections, making the skin look smoother, best for shooting women. Hard light works better for shooting men, making them look gritty and weathered. Although not everyone want’s to look like Rambo, hard light can make the subject look more imposing.

Sometimes you’ll be in a situation when you can’t control the light, but knowing how you can manipulate it to soften or lighten shadows is another weapon in a photographer’s arsenal.