Where to start on this thorny topic? Why choose RAW over jpg? One of the reasons is the amount colour information that recorded.

Take a look at these two images of the Sunseeker 40m:

One is processed RAW images, one a Jpg from the camera, I think it’s clear to see which is which.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves yet. We first need to think about the way images are collected.

Digital cameras use a sensor to record the colour information of the scene seen through the lens. Coloured light is made out of three components red, green and blue. If you’re old enough, think about the big Cathode Ray Tube televisions, if you looked very closely at them you would see the little red, green and blue blocks; these made up the picture by shining red, blue and green light out at different intensities. In a very, very simplistic way the camera sensor works in reverse, they capture the light and convert it to numbers.

The actual make up of sensors vary with make and model and type of camera, but put simply the red, green and blue blocks are either three separate blocks which record the intensity of each colour light landing on it individually, or as one individual block which records the three colours in one go. That block is a pixel. A camera’s megapixel count is the number of million pixels on the sensor.

Light hitting the sensor is converted into a voltage from each pixel. This voltage is converted into red, green and blue values. But what has this got to do with RAW and jpg images?

It’s all into how the colour information is saved. A jpg is known as an 8 bit image, meaning each channel: red, green or blue (or cyan, magenta, yellow or black if you’re printing) is made from an 8 digit long binary number. A “bit” is a binary digit, techy speak for either a 0 or 1. 1 bit would one digit long and would be 0 or 1, say black or white.

2 bits would be two digits long and could be 00, 01, 10, 11, or black black, black white, white black, white white.

Don’t worry I’m not going to go all the way to 8 bits like this, to work 8 bits out it’s: 2 (digits 0 or 1) raised to the power of 8 = 256 (so 2^8=256). So there are 256 steps or levels between black and white, from no light to full light, empty cup to full cup. As I mentioned up there, light is made up of red, green and blue. In an 8 bit image each of these primary colours (or channels) is split up into a value from 0-255 (or a total of 256 different levels because 0 is also a level). Every colour has a value which is a mixture of red, green and blue, so values of R:182 G:201 B:216 will give you a light blue colour.

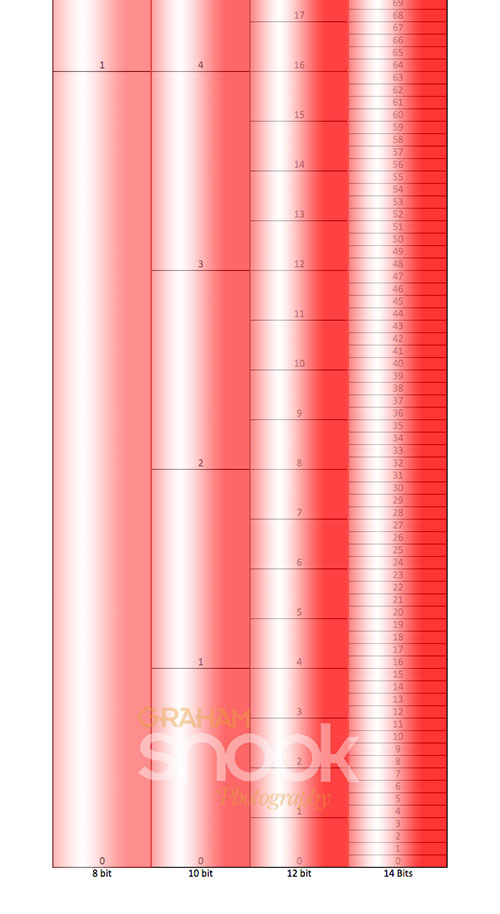

If you imagine three measuring cylinders of coloured water (red, green and blue) all with 100 litres capacity, each cylinder has 256 marks on each the cylinder at equal increments from 0-255 (each mark is 1/256 of the cylinder’s capacity). The only rule is the level of water can only be read at the nearest mark. So for our light blue one would see the red water at mark 182, green at mark 201 and blue at mark 216.

This is how jpg images are made up, each channel can only be spilt into 1 of 256 levels, giving a total of 16.7 million colours (256 x 256 x 256 = 16,777,216). Each pixel has a value made from the RGB value, groups of pixels with the same value next to each other are recorded as such, so instead of mapping each individual pixel, Jpgs compress and map the area and gives it a colour value. The higher the compression and lower quality the more similar pixels are grouped and mapped together this makes for lower quality and smaller file sizes. Jpgs are compressed and therefore lose quality.

If you’re getting jpg images from your camera, your camera is converting that RAW information and producing the Jpg images you see. You can apply settings in your camera to dictate to the camera how it processes those Jpg images and it will apply your formula to each an every image. Compression, white balance, sharpening, saturation are all applied to every image. But not all images are the same, and what the camera thinks is the correct white balance etc to apply, might not be right for that particular image.

16 million colours are a lot, but there are many more colours out there and a shift in colour balance or exposure could reduce the number out of 256 that it was possible to record. This is where RAW comes in. RAW images do not compress and lose information but they all need processing.

RAW images can record 10 bits, 12 bits or sometimes 14 bits per channel. So 1024, 4096 or 16384 levels per channel rather than “just” 256. Think about the cylinder again, same 100 litre cylinder, but instead of being marked 256 times, it’s now marked 1024, 4096 or 16384 times! For every single step in an 8 bit image is 64 steps in a 14 bit image. This gives many more different levels where the colour can be measured from. Here’s a close up of what the bottom of our imaginary cylinders would look like:

On the left is the 8 bit channel going from 0-255, next is the 10 bit from 0-1023, 12 bit from 0-4095 and 14 bit from 0-16383. It should give you some idea of how much more colour information is recorded in RAW images.

Once an image has been recorded in 8 bit, that’s your lot, you’ve lost a lot of colour information. However it’s not all doom and gloom jpgs are quicker to handle and the results from them can still be very good. As long as they are exposed properly a jpg can look great, besides there are few processes that can output 14 or 16 bit images.

That extra colour information in RAW images takes up space, making files large, even with a fast computer everything takes longer. Consider opening a 8 mb jpg compared to a 27 mb RAW file, multiply that by the thousand and you can see where the day goes.

There are however many pieces of software which handle the extra colour information and can be used to bring out the best in an image, but only if it’s there to begin with. All that colour information is recorded and makes the graduation of colour smoother. It’s also possible to correct many things afterwards as you could see at the top of this post. That’s not to say the jpg couldn’t be corrected to be similar, but the RAW gives more options available. With such flexibility it makes shooting RAW popular with amateur photographers; unless you fluff up the exposure very badly you can still get a usable image.

Having the safety net of shooting RAW does little to encourage getting things right in the first place. If an 8 bit image only needs 256 levels per channel and can still look great, then it matters little where any of those 256 layers are taken from if you have 4096 or 16,000 odd to choose from.

From a professional point of view the extra quality it’s possible to get from a RAW image and the versatility they give the photographer is unbeatable.

Keep in touch with regular updates via LinkedIn on Graham Snook Photography’s company page

Or like Graham Snook Photography on Facebook